Who Gets to Play? Enfranchisement and Party System Consolidation in Central Eastern Europe

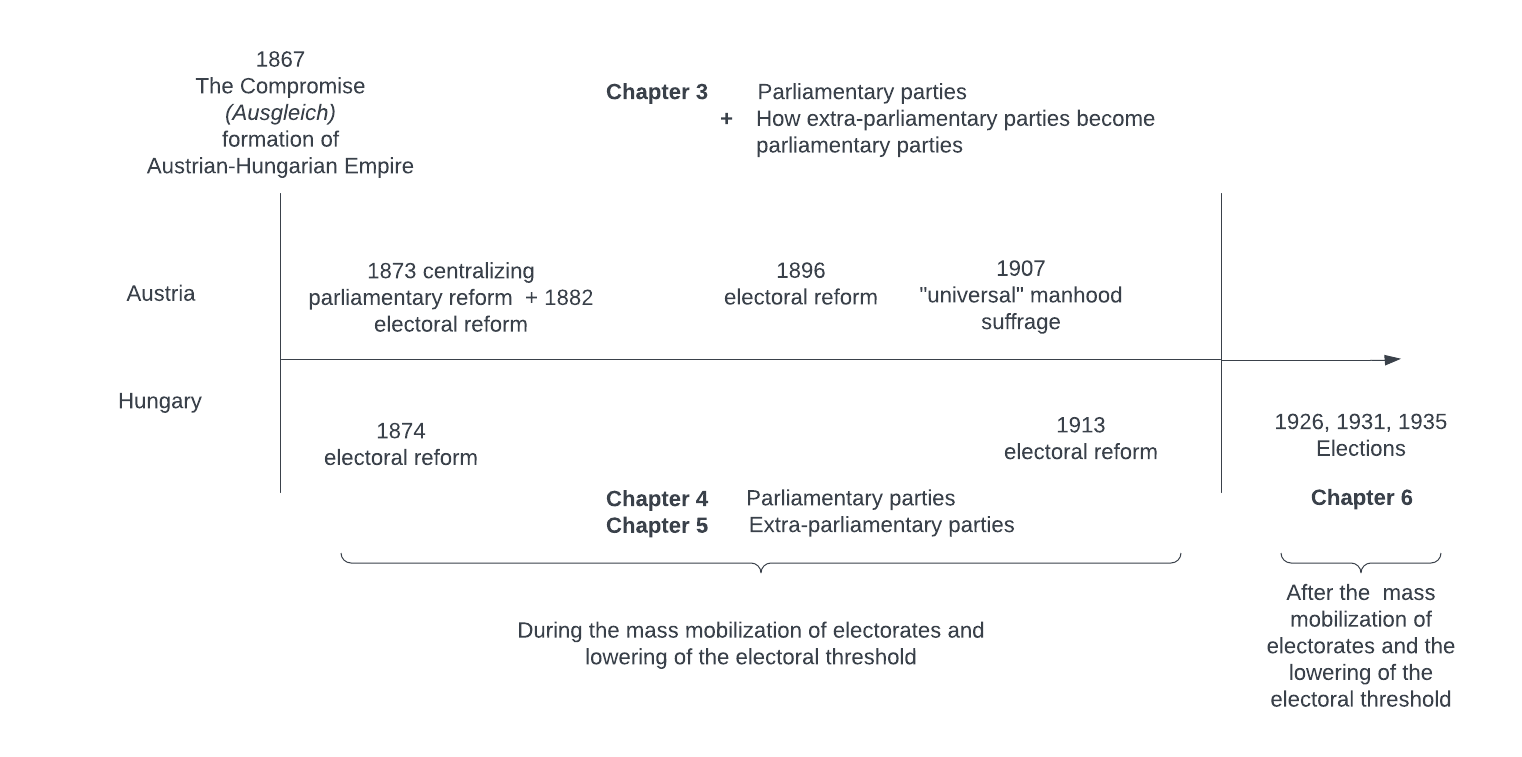

My book project aims to provide an explanation for the origins and persistence of nationalist politics in European party systems. The first half of the book delves into the strategies employed by autocratic rulers to maintain their power during the democratization process by controlling participation in the democratic game. In contrast, the second half explores the impact of disenfranchisement on the mobilization of extra-parliamentary parties in civil society throughout the same period. By examining these aspects together, I aim to elucidate how parties, as key components of party systems, manage to survive democratization and shape the divisions within democratic politics.

The first half of the bookinvestigates the reasons behind parliamentary elites progressively lowering the inclusion threshold during the long process of democratization. Specifically, I show why, when, and how different groups of voters were granted the right to participate by parliamentary parties, considering two distinct types of threats faced by parliamentary elites—organized national minorities and organized working class. Through quantitative analyses, I demonstrate that working-class agitation was not an essential or sufficient condition for extending suffrage, even in the case of universal male suffrage. Instead, increased political competition among parliamentary parties prompted elites to gradually liberalize electoral laws strategically to include specific groups, thus ensuring a minimum-winning coalition. However, in a context where ideological differences defined the contrast between incumbent and opposition parties, the nature of the threat experienced by incumbent parties—either to economic or national order—left a lasting impact on constitutional law. Through an analytical historical narrative, I reveal how incumbent parliamentary parties utilized various requirements in electoral laws to selectively include or exclude voters throughout the democratization process.

The second half of the book focuses on the response of parties that were excluded from parliamentary representation during democratization. I propose a mechanism through which these extra-parliamentary parties managed to survive despite lacking access to state resources or parliamentary power. I introduce the concept of Associational Endowments, which highlights how these parties formed voter-party connections through their physical civil associations. During this period, voluntary associations, many of which were affiliated with extra-parliamentary parties, acted as substitutes for the state in providing social services and goods to the disenfranchised population in the pre-War era. To test my hypotheses, I analyze data from the Kingdom of Hungary (1878-1945) and Austrian Silesia (1867-1944), utilizing hierarchical linear models and newly collected, digitized, and hand-coded data on over 34,000 civil associations. I argue that voter-party linkages were formed during the democratization period itself, rather than after democratization, and these linkages were crucial for parties to survive and establish themselves within the party systems following the introduction of universal male suffrage.

As incumbent parliamentary parties strategically expanded the franchise to safeguard against growing threats from within and outside the parliamentary sphere, the cleavage structure of emerging party systems was shaped by the survival of grassroots movements and parties during the pre-democratic era. If the surviving parties' associations had exclusive membership criteria, such as restrictions based on national identity, occupation, or class, these issues tended to dominate the party system.

I recently wrote a brief overview of Chapters 5 and 6 of the manuscript for the Newsletter for the Comparative Politics Section of APSA. "The Origins of Nationalist Constituencies: The Interests that Mobilized the Passions" (with references)

The manuscript is based on my dissertation research and refines several data sources, including a directory of rabbis in the Kingdom of Hungary (used to differentiate between Jewish denominations), data from over 30,000 civil associations in Austrian Silesia (to study how parties survived the lowering of the electoral threshold in regions with relatively homogeneous labour movements in the 19th century), and improved control measures based on an ongoing census digitization project from the interwar period. I also expand on the methodological rationale behind cross-regional comparisons in social science research, highlighting their appropriateness for studying mechanisms and processes, or when outcomes are not the sole focus.

I tentatively scheduled a book conference for January 17, 2025.

You can find the table of contents for my dissertation here, which will demonstrate how my inclination towards rational choice thinking informed my study and understanding of sociological issues in politics across different periods and locations.

I did not exactly have a linear path through graduate school; I had a lot of help. So, here are the acknowledgements and the many people who made my dissertation work possible Thank you to the people who cared enough about me and this project to help it come to fruition at the dissertation stage.

My book project aims to provide an explanation for the origins and persistence of nationalist politics in European party systems. The first half of the book delves into the strategies employed by autocratic rulers to maintain their power during the democratization process by controlling participation in the democratic game. In contrast, the second half explores the impact of disenfranchisement on the mobilization of extra-parliamentary parties in civil society throughout the same period. By examining these aspects together, I aim to elucidate how parties, as key components of party systems, manage to survive democratization and shape the divisions within democratic politics.

The first half of the bookinvestigates the reasons behind parliamentary elites progressively lowering the inclusion threshold during the long process of democratization. Specifically, I show why, when, and how different groups of voters were granted the right to participate by parliamentary parties, considering two distinct types of threats faced by parliamentary elites—organized national minorities and organized working class. Through quantitative analyses, I demonstrate that working-class agitation was not an essential or sufficient condition for extending suffrage, even in the case of universal male suffrage. Instead, increased political competition among parliamentary parties prompted elites to gradually liberalize electoral laws strategically to include specific groups, thus ensuring a minimum-winning coalition. However, in a context where ideological differences defined the contrast between incumbent and opposition parties, the nature of the threat experienced by incumbent parties—either to economic or national order—left a lasting impact on constitutional law. Through an analytical historical narrative, I reveal how incumbent parliamentary parties utilized various requirements in electoral laws to selectively include or exclude voters throughout the democratization process.

The second half of the book focuses on the response of parties that were excluded from parliamentary representation during democratization. I propose a mechanism through which these extra-parliamentary parties managed to survive despite lacking access to state resources or parliamentary power. I introduce the concept of Associational Endowments, which highlights how these parties formed voter-party connections through their physical civil associations. During this period, voluntary associations, many of which were affiliated with extra-parliamentary parties, acted as substitutes for the state in providing social services and goods to the disenfranchised population in the pre-War era. To test my hypotheses, I analyze data from the Kingdom of Hungary (1878-1945) and Austrian Silesia (1867-1944), utilizing hierarchical linear models and newly collected, digitized, and hand-coded data on over 34,000 civil associations. I argue that voter-party linkages were formed during the democratization period itself, rather than after democratization, and these linkages were crucial for parties to survive and establish themselves within the party systems following the introduction of universal male suffrage.

As incumbent parliamentary parties strategically expanded the franchise to safeguard against growing threats from within and outside the parliamentary sphere, the cleavage structure of emerging party systems was shaped by the survival of grassroots movements and parties during the pre-democratic era. If the surviving parties' associations had exclusive membership criteria, such as restrictions based on national identity, occupation, or class, these issues tended to dominate the party system.

I recently wrote a brief overview of Chapters 5 and 6 of the manuscript for the Newsletter for the Comparative Politics Section of APSA. "The Origins of Nationalist Constituencies: The Interests that Mobilized the Passions" (with references)

The manuscript is based on my dissertation research and refines several data sources, including a directory of rabbis in the Kingdom of Hungary (used to differentiate between Jewish denominations), data from over 30,000 civil associations in Austrian Silesia (to study how parties survived the lowering of the electoral threshold in regions with relatively homogeneous labour movements in the 19th century), and improved control measures based on an ongoing census digitization project from the interwar period. I also expand on the methodological rationale behind cross-regional comparisons in social science research, highlighting their appropriateness for studying mechanisms and processes, or when outcomes are not the sole focus.

I tentatively scheduled a book conference for January 17, 2025.

You can find the table of contents for my dissertation here, which will demonstrate how my inclination towards rational choice thinking informed my study and understanding of sociological issues in politics across different periods and locations.

I did not exactly have a linear path through graduate school; I had a lot of help. So, here are the acknowledgements and the many people who made my dissertation work possible Thank you to the people who cared enough about me and this project to help it come to fruition at the dissertation stage.